In this tutorial we are going to see how to create a CSS animation and trigger it every time we click on a button. We’re going to use pure JavaScript. We’re not going to use jQuery because it’s not really needed and as we’ve seen in a previous blog post jQuery makes our scripts slower so avoiding it whenever possible will transform our code to be more efficient even if it may take a few more lines to achieve the same thing.

This example’s use case is a pretty common one, you have some data displayed to the user via a grid, a chart or simply an unordered list and that data may change overtime so you want to give the user the change to reload the data again from the server asynchronously. Usually for that kind of task you will need to employ a user-friendly icon button and not just throw a “Refresh” button. Something like this:

looks way more slick and increases the UX points of your site. The reason for this is that the user prefers to scan the page instead of reading it so removing unwanted text from action buttons and filters actually makes the browsing experience faster and more pleasant. Adding to that, users find it easier to use an interface that seems familiar to them. A refresh button like the one above is something that the user sees and utilizes in a regular basis in other applications like the operating system (especially mobile OSes) and the browser itself.

Enough talking, let’s get to the code. We’re obviously going to need a button and a refresh icon. We get the icon from FontAwesome (https://fontawesome.io/icons/) and style (using Sass of course) the button a bit to remove borders, make its background-color transparent, put a nice color to the refresh button and change the cursor to the “hand pointer” when the user hovers over the button.

Ignore the animation stuff for now and focus on the icon-btn class used to render the button. We’ll get to the animation mixins shortly

When it comes to animations that need to support a variety of browser versions we tend to get lost in the chaos of vendor specific prefixed but Sass, as always, comes to the rescue. To create the animation we use the @keyframes keyword and state that we want our animation to rotate the icon 360 degrees.The @-webkit- prefix is used to ensure Safari 4.0-8.0 compatibility.

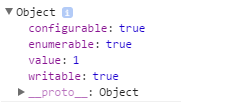

Then we need a class that will apply the animation to the icon, let’s name it ‘spin-animation’. Every time we apply this class to the icon the icon will spin. We need to provide 3 details to the browser’s animation engine:

– The animation name, spin

– The animation duration, say, 0.5 seconds,

– The animation timing function. For this example we set it to ‘ease-in’ so our animation starts slowly and then builds up speed fast.

To include all possible vendor prefixed we create a mixin for each of these properties, animation-name mixin, animation-duration mixin and animation-timing-function mixin. We also create one fourth mixin that takes three parameters, the animation name, the animation duration and the animation-timing-function and passes them to the other three mixins. That way our code becomes extremely clean because we only need to include one mixin to our .spin-animation class in order for it to work as expected.

Now to the JavaScript part. Check the updated fiddle below that also presents the JavaScript code:

Every time the user clicks on the button, the icon should spin. To do that we listen for the button’s ‘click’ event and add the ‘spin-animation’ class to the icon. If we were to stop at this point, and not include the call to setTimeout, the code would actually work. The icon would spin on button click. But it would spin only once. The next click wouldn’t cause the button to spin. You can simulate this behavior by commenting out the call to setTimeout in the above fiddle. The reason why the second (and the third, and the fourth…) click fails is because the class is already set and the animation iteration count is by default set to 1 (Setting it to infinite would cause the button to spin eternally). So what do we do? We remove it after the animation is complete!. setTimeout ensures that upon animation completion after 500ms, which can be translated to 0.5s which is the animation-duration, the spin-animation class will be removed from the icon thus allowing the button to spin when the class is added again in the future.

That’s how you can work with animations that need to run for a finite number of iterations when triggered by some DOM event. That’s all for today! Bye!